Difference between revisions of "Directory:Jon Awbrey/Papers/Dynamics And Logic"

Jon Awbrey (talk | contribs) (→Note 16: markup) |

Jon Awbrey (talk | contribs) (→Note 16: markup) |

||

| Line 3,221: | Line 3,221: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | It is part of the definition of a group that the 3-adic relation <math>L \subseteq G^3</math> is actually a function <math>L : G \times G \to G.</math> It is from this functional perspective that we can see an easy way to derive the two regular representations. Since we have a function of the type <math>L : G \times G \to G,</math> we can define a couple of substitution operators: | |

| − | It is part of the definition of a group that the 3-adic | ||

| − | relation L | ||

| − | It is from this functional perspective that we can see | ||

| − | an easy way to derive the two regular representations. | ||

| − | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="6" width="90%" | |

| − | + | | valign="top" | 1. | |

| + | | <math>\operatorname{Sub}(x, (\underline{~~}, y))</math> puts any specified <math>x\!</math> into the empty slot of the rheme <math>(\underline{~~}, y),</math> with the effect of producing the saturated rheme <math>(x, y)\!</math> that evaluates to <math>xy.\!</math> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top" | 2. | ||

| + | | <math>\operatorname{Sub}(x, (y, \underline{~~}))</math> puts any specified <math>x\!</math> into the empty slot of the rheme <math>(y, \underline{~~}),</math> with the effect of producing the saturated rheme <math>(y, x)\!</math> that evaluates to <math>yx.\!</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | 1 | + | In (1) we consider the effects of each <math>x\!</math> in its practical bearing on contexts of the form <math>(\underline{~~}, y),</math> as <math>y\!</math> ranges over <math>G,\!</math> and the effects are such that <math>x\!</math> takes <math>(\underline{~~}, y)</math> into <math>xy,\!</math> for <math>y\!</math> in <math>G,\!</math> all of which is notated as <math>x = \{ (y : xy) ~|~ y \in G \}.</math> The pairs <math>(y : xy)\!</math> can be found by picking an <math>x\!</math> from the left margin of the group operation table and considering its effects on each <math>y\!</math> in turn as these run across the top margin. This aspect of pragmatic definition we recognize as the regular ante-representation: |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="6" width="90%" | |

| − | + | | align="center" | | |

| − | + | <math>\begin{matrix} | |

| − | + | \operatorname{e} | |

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | \operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | \operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | \operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | In ( | + | In (2) we consider the effects of each <math>x\!</math> in its practical bearing on contexts of the form <math>(y, \underline{~~}),</math> as <math>y\!</math> ranges over <math>G,\!</math> and the effects are such that <math>x\!</math> takes <math>(y, \underline{~~})</math> into <math>yx,\!</math> for <math>y\!</math> in <math>G,\!</math> all of which is notated as <math>x = \{ (y : yx) ~|~ y \in G \}.</math> The pairs <math>(y : yx)\!</math> can be found by picking an <math>x\!</math> from the top margin of the group operation table and considering its effects on each <math>y\!</math> in turn as these run down the left margin. This aspect of pragmatic definition we recognize as the regular post-representation: |

| − | practical bearing on contexts of the form < | ||

| − | as y ranges over G, and the effects are such that | ||

| − | x takes < | ||

| − | is | ||

| − | The pairs <y : | ||

| − | from the | ||

| − | and considering its effects on each y in turn as | ||

| − | these run | ||

| − | pragmatic definition we recognize as the regular | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="6" width="90%" | |

| + | | align="center" | | ||

| + | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| + | \operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | \operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | \operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | \\[4pt] | ||

| + | \operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & = & \operatorname{e}\!:\!\operatorname{h} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{f}\!:\!\operatorname{g} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{g}\!:\!\operatorname{f} | ||

| + | & + & \operatorname{h}\!:\!\operatorname{e} | ||

| + | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | + | If the ante-rep looks the same as the post-rep, now that I'm writing them in the same dialect, that is because <math>V_4\!</math> is abelian (commutative), and so the two representations have the very same effects on each point of their bearing. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | If the ante-rep looks the same as the post-rep, | ||

| − | now that I'm writing them in the same dialect, | ||

| − | that is because V_4 is abelian (commutative), | ||

| − | and so the two representations have the very | ||

| − | same effects on each point of their bearing. | ||

| − | |||

==Note 17== | ==Note 17== | ||

Revision as of 00:04, 15 June 2009

Note 1

I am going to excerpt some of my previous explorations on differential logic and dynamic systems and bring them to bear on the sorts of discrete dynamical themes that we find of interest in the NKS Forum. This adaptation draws on the "Cactus Rules", "Propositional Equation Reasoning Systems", and "Reductions Among Relations" threads, and will in time be applied to the "Differential Analytic Turing Automata" thread:

One of the first things that you can do, once you have a moderately functional calculus for boolean functions or propositional logic, whatever you choose to call it, is to start thinking about, and even start computing, the differentials of these functions or propositions.

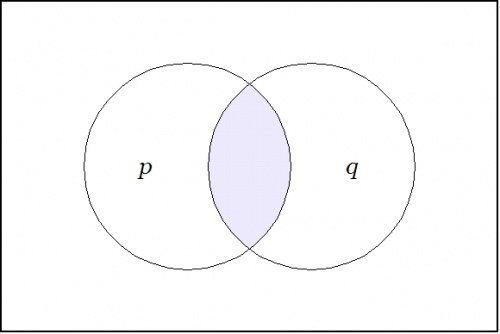

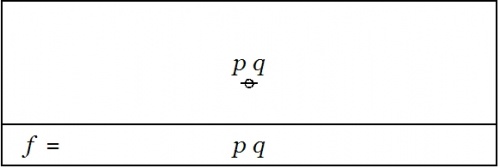

Let us start with a proposition of the form \(p ~\operatorname{and}~ q\) that is graphed as two labels attached to a root node:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | p q | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | p and q | o-------------------------------------------------o |

Written as a string, this is just the concatenation "\(p~q\)".

The proposition \(pq\!\) may be taken as a boolean function \(f(p, q)\!\) having the abstract type \(f : \mathbb{B} \times \mathbb{B} \to \mathbb{B},\) where \(\mathbb{B} = \{ 0, 1 \}\) is read in such a way that \(0\!\) means \(\operatorname{false}\) and \(1\!\) means \(\operatorname{true}.\)

In this style of graphical representation, the value \(\operatorname{true}\) looks like a blank label and the value \(\operatorname{false}\) looks like an edge.

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | true | o-------------------------------------------------o |

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | o | | | | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | false | o-------------------------------------------------o |

Back to the proposition \(pq.\!\) Imagine yourself standing in a fixed cell of the corresponding venn diagram, say, the cell where the proposition \(pq\!\) is true, as shown here:

|

Now ask yourself: What is the value of the proposition \(pq\!\) at a distance of \(\operatorname{d}p\) and \(\operatorname{d}q\) from the cell \(pq\!\) where you are standing?

Don't think about it — just compute:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | dp o o dq | | / \ / \ | | p o---@---o q | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | (p, dp) (q, dq) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

To make future graphs easier to draw in ASCII, I will use devices like @=@=@ and o=o=o to identify several nodes into one, as in this next redrawing:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | p dp q dq | | o---o o---o | | \ | | / | | \ | | / | | \| |/ | | @=@ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | (p, dp) (q, dq) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

However you draw it, these expressions follow because the expression \(p + \operatorname{d}p,\) where the plus sign indicates addition in \(\mathbb{B},\) that is, addition modulo 2, and thus corresponds to the exclusive disjunction operation in logic, parses to a graph of the following form:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | p dp | | o---o | | \ / | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | (p, dp) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

Next question: What is the difference between the value of the proposition \(pq\!\) "over there" and the value of the proposition \(pq\!\) where you are, all expressed in the form of a general formula, of course? Here is the appropriate formulation:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | p dp q dq | | o---o o---o | | \ | | / | | \ | | / | | \| |/ p q | | o=o-----------o | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | ((p, dp)(q, dq), p q) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

There is one thing that I ought to mention at this point: Computed over \(\mathbb{B},\) plus and minus are identical operations. This will make the relation between the differential and the integral parts of the appropriate calculus slightly stranger than usual, but we will get into that later.

Last question, for now: What is the value of this expression from your current standpoint, that is, evaluated at the point where \(pq\!\) is true? Well, substituting \(1\!\) for \(p\!\) and \(1\!\) for \(q\!\) in the graph amounts to erasing the labels \(p\!\) and \(q\!,\) as shown here:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | dp dq | | o---o o---o | | \ | | / | | \ | | / | | \| |/ | | o=o-----------o | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | \ / | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | (( , dp)( , dq), ) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

And this is equivalent to the following graph:

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | dp dq | | o o | | \ / | | o | | | | | @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | ((dp) (dq)) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

Note 2

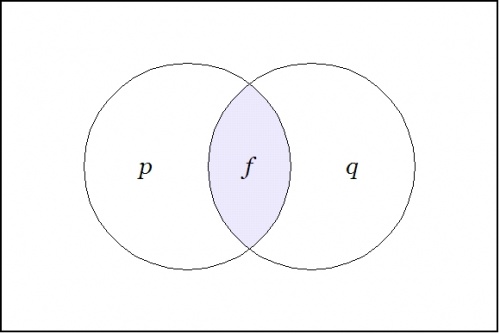

We have just met with the fact that the differential of the and is the or of the differentials.

|

\(p ~\operatorname{and}~ q \quad \xrightarrow{~\operatorname{Diff}~} \quad \operatorname{d}p ~\operatorname{or}~ \operatorname{d}q\) |

o-------------------------------------------------o | | | dp dq | | o o | | \ / | | o | | p q | | | @ --Diff--> @ | | | o-------------------------------------------------o | p q --Diff--> ((dp) (dq)) | o-------------------------------------------------o |

It will be necessary to develop a more refined analysis of that statement directly, but that is roughly the nub of it.

If the form of the above statement reminds you of De Morgan's rule, it is no accident, as differentiation and negation turn out to be closely related operations. Indeed, one can find discussions of logical difference calculus in the Boole–De Morgan correspondence and Peirce also made use of differential operators in a logical context, but the exploration of these ideas has been hampered by a number of factors, not the least of which has been the lack of a syntax that was adequate to handle the complexity of expressions that evolve.

Let us run through the initial example again, this time attempting to interpret the formulas that develop at each stage along the way.

We begin with a proposition or a boolean function \(f(p, q) = pq.\!\)

|

|

A function like this has an abstract type and a concrete type. The abstract type is what we invoke when we write things like \(f : \mathbb{B} \times \mathbb{B} \to \mathbb{B}\) or \(f : \mathbb{B}^2 \to \mathbb{B}.\) The concrete type takes into account the qualitative dimensions or the "units" of the case, which can be explained as follows.

| Let \(P\!\) be the set of values \(\{ \texttt{(} p \texttt{)},~ p \} ~=~ \{ \operatorname{not}~ p,~ p \} ~\cong~ \mathbb{B}.\) |

| Let \(Q\!\) be the set of values \(\{ \texttt{(} q \texttt{)},~ q \} ~=~ \{ \operatorname{not}~ q,~ q \} ~\cong~ \mathbb{B}.\) |

Then interpret the usual propositions about \(p, q\!\) as functions of the concrete type \(f : P \times Q \to \mathbb{B}.\)

We are going to consider various operators on these functions. Here, an operator \(\operatorname{F}\) is a function that takes one function \(f\!\) into another function \(\operatorname{F}f.\)

The first couple of operators that we need to consider are logical analogues of the pair that play a founding role in the classical finite difference calculus, namely:

| The difference operator \(\Delta,\!\) written here as \(\operatorname{D}.\) |

| The enlargement" operator \(\Epsilon,\!\) written here as \(\operatorname{E}.\) |

These days, \(\operatorname{E}\) is more often called the shift operator.

In order to describe the universe in which these operators operate, it is necessary to enlarge the original universe of discourse. Starting from the initial space \(X = P \times Q,\) its (first order) differential extension \(\operatorname{E}X\) is constructed according to the following specifications:

|

\(\begin{array}{rcc} \operatorname{E}X & = & X \times \operatorname{d}X \end{array}\) |

where:

|

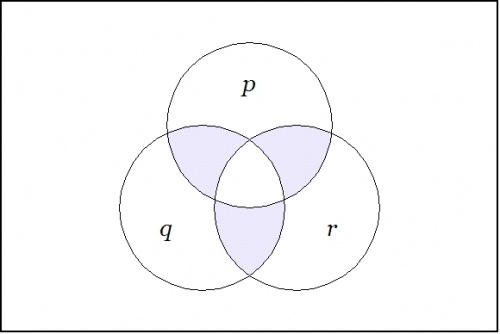

\(\begin{array}{rcc} X & = & P \times Q \'"`UNIQ-MathJax1-QINU`"' Amazing! =='"`UNIQ--h-10--QINU`"'Note 11== We have been contemplating functions of the type \(f : X \to \mathbb{B}\) and studying the action of the operators \(\operatorname{E}\) and \(\operatorname{D}\) on this family. These functions, that we may identify for our present aims with propositions, inasmuch as they capture their abstract forms, are logical analogues of scalar potential fields. These are the sorts of fields that are so picturesquely presented in elementary calculus and physics textbooks by images of snow-covered hills and parties of skiers who trek down their slopes like least action heroes. The analogous scene in propositional logic presents us with forms more reminiscent of plateaunic idylls, being all plains at one of two levels, the mesas of verity and falsity, as it were, with nary a niche to inhabit between them, restricting our options for a sporting gradient of downhill dynamics to just one of two: standing still on level ground or falling off a bluff. We are still working well within the logical analogue of the classical finite difference calculus, taking in the novelties that the logical transmutation of familiar elements is able to bring to light. Soon we will take up several different notions of approximation relationships that may be seen to organize the space of propositions, and these will allow us to define several different forms of differential analysis applying to propositions. In time we will find reason to consider more general types of maps, having concrete types of the form \(X_1 \times \ldots \times X_k \to Y_1 \times \ldots \times Y_n\) and abstract types \(\mathbb{B}^k \to \mathbb{B}^n.\) We will think of these mappings as transforming universes of discourse into themselves or into others, in short, as transformations of discourse. Before we continue with this intinerary, however, I would like to highlight another sort of differential aspect that concerns the boundary operator or the marked connective that serves as one of the two basic connectives in the cactus language for ZOL. For example, consider the proposition \(f\!\) of concrete type \(f : P \times Q \times R \to \mathbb{B}\) and abstract type \(f : \mathbb{B}^3 \to \mathbb{B}\) that is written \(\texttt{(} p, q, r \texttt{)}\) in cactus syntax. Taken as an assertion in what Peirce called the existential interpretation, the proposition \(\texttt{(} p, q, r \texttt{)}\) says that just one of \(p, q, r\!\) is false. It is instructive to consider this assertion in relation to the logical conjunction \(pqr\!\) of the same propositions. A venn diagram of \(\texttt{(} p, q, r \texttt{)}\) looks like this:

In relation to the center cell indicated by the conjunction \(pqr,\!\) the region indicated by \(\texttt{(} p, q, r \texttt{)}\) is comprised of the adjacent or bordering cells. Thus they are the cells that are just across the boundary of the center cell, reached as if by way of Leibniz's minimal changes from the point of origin, in this case, \(pqr.\!\) More generally speaking, in a \(k\!\)-dimensional universe of discourse that is based on the alphabet of features \(\mathcal{X} = \{ x_1, \ldots, x_k \},\) the same form of boundary relationship is manifested for any cell of origin that one chooses to indicate. One way to indicate a cell is by forming a logical conjunction of positive and negative basis features, that is, by constructing an expression of the form \(e_1 \cdot \ldots \cdot e_k,\) where \(e_j = x_j ~\text{or}~ e_j = \texttt{(} x_j \texttt{)},\) for \(j = 1 ~\text{to}~ k.\) The proposition \(\texttt{(} e_1, \ldots, e_k \texttt{)}\) indicates the disjunctive region consisting of the cells that are just next door to \(e_1 \cdot \ldots \cdot e_k.\) Note 12

One other subject that it would be opportune to mention at this point, while we have an object example of a mathematical group fresh in mind, is the relationship between the pragmatic maxim and what are commonly known in mathematics as representation principles. As it turns out, with regard to its formal characteristics, the pragmatic maxim unites the aspects of a representation principle with the attributes of what would ordinarily be known as a closure principle. We will consider the form of closure that is invoked by the pragmatic maxim on another occasion, focusing here and now on the topic of group representations. Let us return to the example of the four-group \(V_4.\!\) We encountered this group in one of its concrete representations, namely, as a transformation group that acts on a set of objects, in this case a set of sixteen functions or propositions. Forgetting about the set of objects that the group transforms among themselves, we may take the abstract view of the group's operational structure, for example, in the form of the group operation table copied here:

This table is abstractly the same as, or isomorphic to, the versions with the \(\operatorname{E}_{ij}\) operators and the \(\operatorname{T}_{ij}\) transformations that we took up earlier. That is to say, the story is the same, only the names have been changed. An abstract group can have a variety of significantly and superficially different representations. But even after we have long forgotten the details of any particular representation there is a type of concrete representations, called regular representations, that are always readily available, as they can be generated from the mere data of the abstract operation table itself. To see how a regular representation is constructed from the abstract operation table, select a group element from the top margin of the Table, and "consider its effects" on each of the group elements as they are listed along the left margin. We may record these effects as Peirce usually did, as a logical aggregate of elementary dyadic relatives, that is, as a logical disjunction or boolean sum whose terms represent the ordered pairs of \(\operatorname{input} : \operatorname{output}\) transactions that are produced by each group element in turn. This forms one of the two possible regular representations of the group, in this case the one that is called the post-regular representation or the right regular representation. It has long been conventional to organize the terms of this logical aggregate in the form of a matrix: Reading "\(+\!\)" as a logical disjunction:

And so, by expanding effects, we get:

|